I’ve spent several weeks struggling with an essay that compares Trump to Hitler. I have yet to find the right way to word it. [I solved this problem. See this.] For now, I want to share a few quotes that are rooted in World War II yet still speak to our present situation.

Quote No. 1

We see ourselves [Poles] as exceptional, ascribe to ourselves moral achievements, a unique contribution to world history. Studies show that people who think this way more readily accept the killing of innocents.

Quote No. 1 comes from Anna Bikont’s The Crime and the Silence, her investigation into the killing of the Jews of Jedwabne, Poland. This tragedy first came to light in Jan Gross’s Neighbors, which I sardonically summarize as the heart-warming story of a small town in Poland where the Poles solved their Jewish problem by herding them into a barn and burning them alive. The “inspiration” for this horror likely came from the nearby town of Radzilow where the same thing occurred three days earlier on July 7, 1941.

Quote No. 2

According to the standards of the time, humane behavior was deviant, and brutality was conformist. For that reason, the entire collection of events known as the ‘Third Reich’ and the violence it produced can be seen as a gigantic experiment, showing what sane people who see themselves as good are capable of if they consider something to be appropriate, sensible, or correct. The proportion of people who were psychologically inclined toward violence, discrimination, and excess totaled, as it does in all other social contexts as well, 5 to 10 percent.

Quote No. 2 (cont’d)

In psychological terms, the inhabitants of the Third Reich were as normal as people in all other societies at all other times. The spectrum of perpetrators was a cross section of normal society. No specific group of people proved immune to the temptation, Günther Anders’s phrase, of ‘inhumanity with impunity.’ The real-life experiment that was the Third Reich did not reduce the variables of personality to absolute zero. But it show them to be of comparatively slight, indeed often negligible, importance.

Quote No. 2 comes from Soldaten: The Secret WWII Transcripts of German POWs by Harold Welzer and Sönke Neitzel. It’s context is obvious. Before we congratulate ourselves for not being like ‘those Nazis’ (or those Poles), we should reacquaint ourselves with American history and our own stories of brutality — the inhumane treatment of enslaved African-Americans (See: The Half Has Never Been Told), the horrors of the devolution of Reconstruction (See:Redemption: The Last Battle of the Civil War), the horrors of lynching (See: Ida Wells,Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases, or Mob Rule in New Orleans) — and the slow-moving genocide of Native Americans. Brutality continues in new forms — African-Americans killed by those who are paid to ‘protect and serve,’ prisoners of war tortured in the name of freedom and democracy, and so on.

The question that keeps me up late at night, even more so since November 8, is how does society come to ‘embrace’ brutality? How does it become part of the normal course of daily life? Of course, this question assumes that societies move from non-brutal to brutal, whereas history shows that there is always a level of brutality in society. Perhaps the question should be, how does society become more brutal? The answer to that is easy. It usually happens slowly, and sometimes imperceptibly, and its imperceptibility is exacerbated by the very human inclination to ignore warning signs, to tend to our own gardens, and to dismiss as insanity the words of those who try to warn others of the impending danger. (You can count me in the ‘insanity’ column, with a heavy dose of ‘canary in the coal mine’ syndrome.)

In 1955, Milton Mayer spoke with ordinary Germans to find out what life looked like from their perspective. How did they come to accept the brutality of the Third Reich? One of the interviewees explains:

Quote No. 3

To live in this process is absolutely not to be able to notice it— please try to believe me—unless one has a much greater degree of political awareness, acuity, than most of us had ever had occasion to develop. Each step was so small, so inconsequential, so well explained or, on occasion, ‘regretted,’ that, unless one were detached from the whole process from the beginning, unless one understood what the whole thing was in principle, what all these ‘little measures’ that no ‘patriotic German’ could resent must some day lead to, one no more saw it developing from day to day than a farmer in his field sees the corn growing. One day it is over his head.

Quote No. 3 comes from Milton Mayer’s, They Thought They Were Free. I believe the point is clear. The corn is growing.

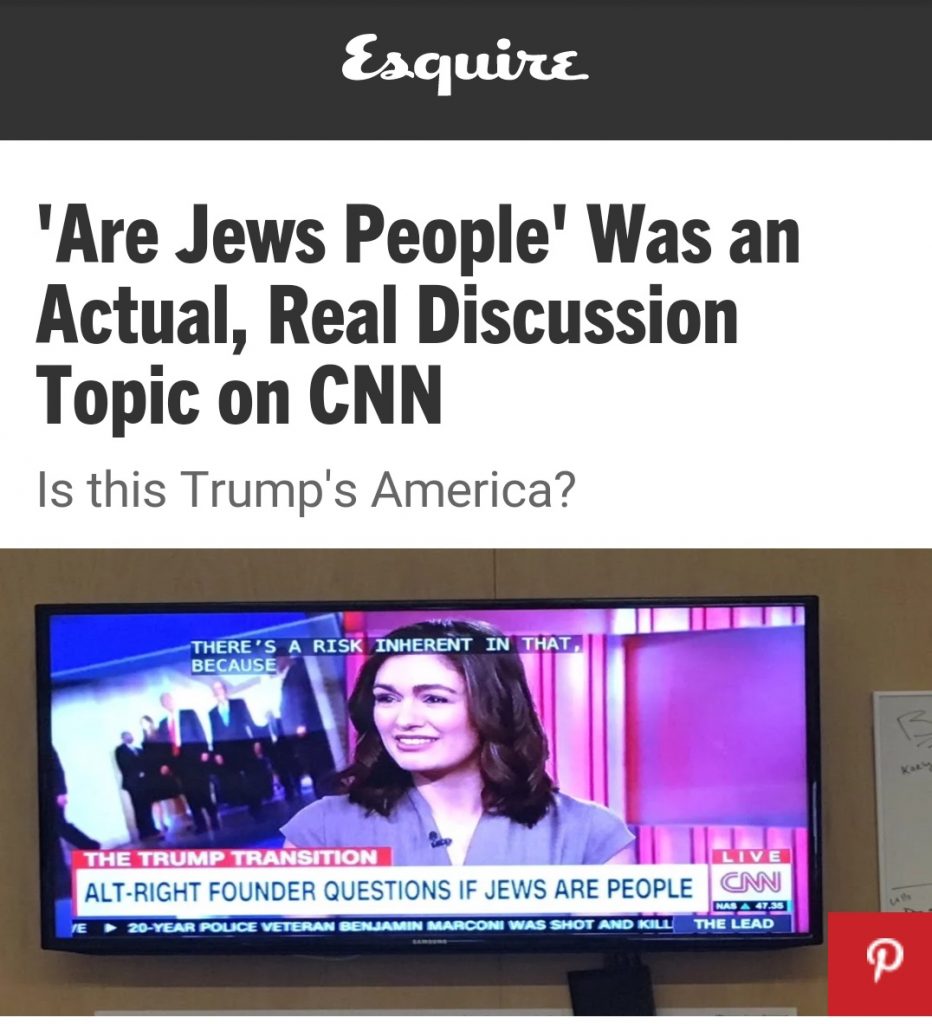

Source: Are Jews People

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.